“I have often wondered what the prey is feeling when it is captured. Often it seems to become completely still in the predator’s jaws, as if it feels no pain. As if nature, at the very end, shows mercy for it.” – Jonathan Franzen, Purity (p. 71)

Book in the Pipeline: Havoc by Tom Kristensen

I distinctly remember Norwegian novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard, in his My Struggle series, writing at length about the 1930 novel Havoc by Danish writer Tom Kristensen, Knausgaard championing the book as one of the most profound works he had read. And indeed, a short quote from Knausgaard makes an appearance on the back cover of the NYRB edition: “Havoc is one of the best novels to ever come out of Scandinavia. As discomforting as it is beautiful, it portrays the fall of a man, and it’s so hypnotically written that you want to fall with him.” Likewise, author Nina Rosenstand calls the novel “the Ulysses as well as the Steppenwolf of Danish literature.” Stretching over 500 pages, Havoc is the story of Ole Jastrau, an enterprising and ambitious young man on the cusp of literary fame. Yet, he also stands on the cusp of an emotional and moral downfall fomented by the disillusionment of his marriage, the burden of fatherhood, and a growing disdain for the commercial and political compromises he’s forced to make at his daytime editorial job. To stave off the encroaching anxieties of his everyday, Ole retreats from reality and into the dark recesses of his mind by way of excessive binge-drinking. “Ah yes, there was something religious about drinking oneself into insensibility,” Ole muses. As the novel unfolds, Ole’s alcoholism grows into an act of reverence, a sacred vocation and vow of self-destruction, fraught with an unceasing, unavailing attempt to taste the sublime infinite at the bottom of his glass. Critic Morten Jensen described Havoc, as “a Danish Inferno, a tortured descent through every circle of hell–and then some.” With a description like that, I simply cannot not read this one.

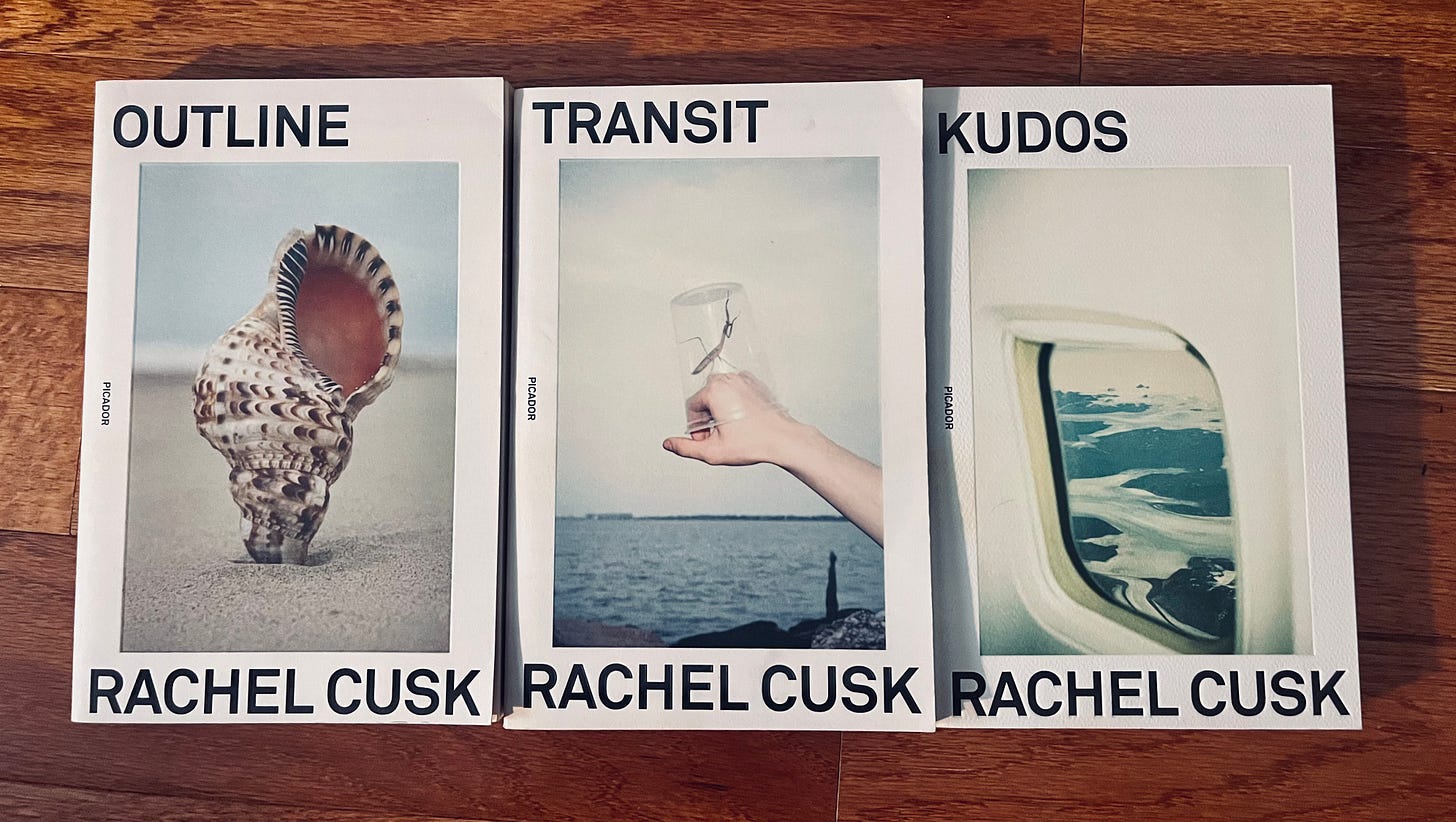

Book Still on the Mind: The Outline Trilogy by Rachel Cusk

This past Tuesday saw the publication of English novelist Rachel Cusk’s new novel Parade, which is already stirring reviews ranging wide across the literary sphere. I personally cannot wait to get my hands on a copy and inevitably be reminded why Rachel Cusk is one of the most interesting writers working today. My introduction to her work was her famed autobiographical Outline Trilogy: Outline (2014), Transit (2016), and Kudos (2018). I read all three over the course of 2020 and ranked the trilogy third in my top ten list of the year. Each of the books follows Faye, a writer and mother who regales her various encounters with strangers, the exchanges that ensue, and the experiences that result, which, as narrator, are filtered through Faye’s perspective yet typically depicted devoid of deeper analysis. It’s almost as if Faye disappears into the words, the sentences, the pages of others’ stories. In Outline, Faye travels to Athens, Greece to teach a creative writing course. In Transit, Faye, recently divorced, has her London apartment renovated as her two sons stay with their father. And in Kudos, Faye attends a writer’s conference as a guest speaker. In each of the novels, Faye remains somewhat aloof, distant from the reader, a neutral vessel and cipher through whom we meet those around her and in so doing, slowly gain a faint outline of Faye herself. Fictionalizing reality in stark, sparing, yet illuminative prose, Rachel Cusk falls right in line with writers like Elizabeth Hardwick, Annie Ernaux, and Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose works sit cemented in the realm of autofiction. And yet still Cusk seems to stand outside such a pantheon, as her Trilogy, structured in a mosaic of descriptive fragments, resembles more a collection of oral histories than a series of connecting cohesive novels, but which reflect at once the instability of memory and the interconnectedness of humanity. The result is a literary achievement which many critics have lauded as a “reinvention” of the modern novel, and with that, it is a certainty that Rachel Cusk is a writer at once to watch and return to.

Rachel Cusk, source: New York Times

Art(ist) of the Week: “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair” by Mary Cassatt (1878)

“Little Girl in a Blue Armchair,” Mary Cassatt, 1878, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Last Friday, I attended the new Mary Cassatt exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was an incredible delight. I finally saw in person one of my favorite works of hers, “In the Loge,” which I wrote about in “The Eighth,” a wondrously, wittily referential work which showcases Cassatt’s brilliant inventiveness. However, I was also able to see another one of her famous works, a painting that first appeared the same year: “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair.” A work much larger than expected, this painting exemplifies Cassatt’s burgeoning relationship with impressionism, expressively highlighting an adoption of a freer form that would become her trademark. In an expansive room with windows glowing in the background, the tilted plane draws viewers to the haphazard arrangement of four large blue chairs situated on beige flooring, each painted in energetic brushwork. A little girl, slumped in the foremost chair rightward the frame, and the small terrier curled up in the chair next to her, remain in quiet, innocent repose. Cassatt’s hallmark ambiguity manifests in this simple moment suspended between rest and play: is the girl bored or exhausted? Content or irritated? Pensive or unthinking? Whichever it is, is left up to the viewer. Cassatt worked on the painting with the assistance of her friend Edgar Degas and, upon finishing, submitted it to the 1878 World’s Fair in Paris, but it was rejected, much to Cassatt’s chagrin. And yet, now, funnily, the painting has become one of Cassatt’s most famous, a sure testament to her talent and lasting legacy in the annals of art history.

“Mary Cassatt at Work,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, 6/14/24

Music(ian) of the Week: “Starvation” by Aurora

On June 7th, Norwegian singer-songwriter Aurora released her highly anticipated fourth studio album, What Happened to the Heart? After listening to the album in its entirety twice during a train ride from Rhode Island back to Philly, I am ever the more convinced that Aurora is one of greatest musical artists working today. She’s a singer-songwriter whose music I’ve long listened to and loved, so much so that I’ve been wary of writing about her, as selecting which of her songs to write about, let alone actually describing them in words, is surely an impossible task. But I would feel remiss if, upon the arrival of her newest wondrous masterwork, I didn’t at least attempt it. The album is the culmination of years’ worth of writing and recording, and with it, I think Aurora has achieved a new height in her musical career. It is eclectic, it is beautiful, it is evocative, it is beatific. It is a work of music that makes me grateful to be here to hear it. Of the many tracks that stood out from the first listen-through, “Starvation,” the fourth single from the album, was most certainly one. Down-filtered drum rolls strike in quick succession in tempo with the tom, as Aurora’s low-registered first verse, in a mellifluous minor melody, sounds the start of “Starvation”: “I miss the touch of human hands on my skin/ Miss the rush of beauty coming from within.” The verse runs as Aurora’s verse amplifies in choral harmony, accompanied with the beating kick. And then, skipping an interlude, she flows straight into chorus: waves surging in muted synths as Aurora cries: “Why do we have to die for us to see the light? / And we hunger for love.” In a strident, near-shrill-like lilt, Aurora propels her vocals upward into her higher range, widening the timbre into a pleasurable piercing resonance, a sublime sound found in many of her other songs and which, for me, is truly singular. The passion that emanates from such a thrust is overwhelming: one can feel, let alone hear, the painful yearning, the desperation in her voice, bolstered by the content of her lyrics. And she carries this passion into the next verse, the next chorus, and still on into crescendo during the interlude, wherein the drums, steady and stalwart, move in tandem with the growing orchestration, rising upward and upward, until the climax comes: hard kicks thumping in perfect succession driving the emphatic apotheosis, the compressed synths aligned in short decay after the hypnotic, technotic beat, the bass thrumming below as Aurora’s high-flying wails peak in the offing. Ahh, it gives me chills! Melodious, messianic, it is a musical metamorphosis in three and a half minutes. What started as a soft though fervent ballad has transformed into a melodic techno tune, the lyrics into a dance, the singer a prophetess. The power this one song possesses transcends the bounds of music, art, lyricism, and moves Aurora, perhaps my favorite artist working today, into a space that is entirely her own. I enthusiastically encourage all to listen to her new album and her entire oeuvre at large. Also, happily, I snagged a ticket to her December show at the Fillmore here in Philly, which I truly cannot wait for. It’ll be my second time seeing her perform.

Aurora

Wild Card: Kung Fun Necktie

Last weekend I went with some friends to a “Post-Punk Party” at Kung Fu Necktie, a bar and live music venue over in Fishtown, here in Philly. Not only did I have an absolutely incredible time dancing my ass off to the sultry sounds of New Order and The Cure, but I was enamored with the place itself, a bar that I had long been wanting to visit. Kung Fu Necktie truly eludes description. Sat somewhere between a dive and dim-lit pub, it is a small space, whose regulars and staff alike don black and bear their ink like escutcheons, emphatic emblems shifting in the red and black shadows inside. Up a short flight of stairs, a narrow entrance opens to a vestibule before the threshold to the bar-sided atrium, booths lining the walls leftward and right, a couple tables idle center floor. A wooden bar snakes down the opposite length of the room, terminating over an incline that flows upward and plateaus to a tiny dance floor before the stage which sleeps under a cavernlike, cathedral-like dome. Rightward center floor hides a little alcove, a DJ booth, to the right of which and back down the incline are three graffiti-filled bathrooms, one with a door so thin, to enter and exit requires a sidewise turn. Perhaps my favorite part of the bar (beside the cheap drinks, great tunes, and vibrant crowd) is that the longer you look into the space, the more you start to notice the strange and almost eerie tiny tchotchkes suspended in various hiding places in the bar, in the lining the walls streaked in Sharpied graffiti and blanketed by varicolored stickers. Near full capacity last weekend, a viscid redolence, tinged wet with sweat and spirits, hung off the vapory air, reminding me so much of some of my favorite bars I used to frequent back in Richmond, particularly Strange Matter and Wonderland, places that held as much personality as the patrons who entered, places at once iconic and iconoclastic. I can say with certainty, my first time at Kung Fu Necktie will surely not be my last.